AIWitness testimony: visual neuroprostheses, AI-mediated perception and the law of evidence

- Volume

- CitationGonzález-Márquez C, Schafer B. AIWitness testimony: visual neuroprostheses, AI-mediated perception and the law of evidence. Law Ethics Technol. 2026(1):0001, https://doi.org/10.55092/let20260001.

- DOI10.55092/let20260001

- CopyrightCopyright2026 by the authors. Published by ELSP.

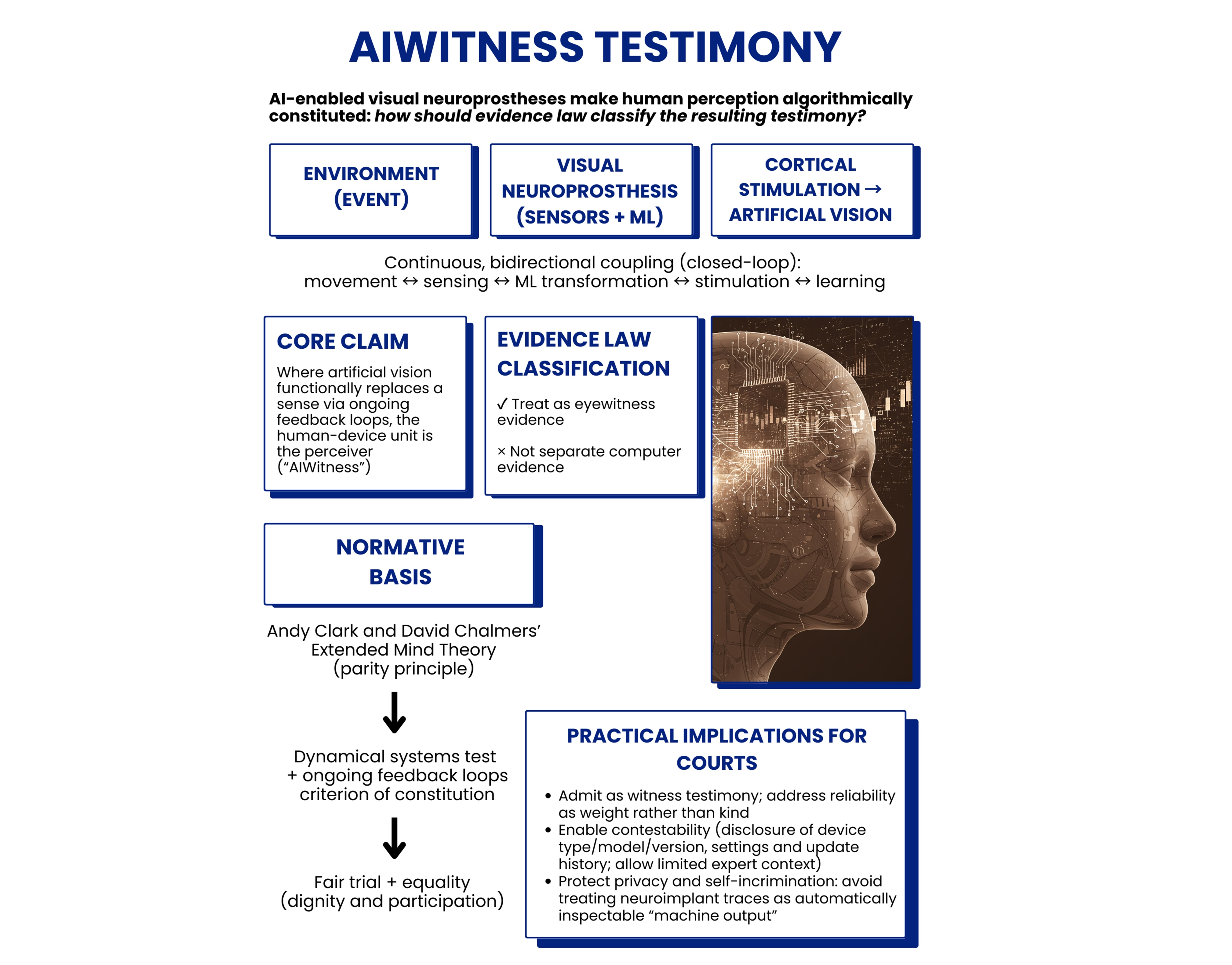

Advances in neurotechnology are developing rapidly, creating challenges for legal systems whose basic categories date back to the 18th and 19th centuries. AI-mediated sensory perception challenges core categories of evidence law. This paper focuses on the distinction between eyewitness and computer evidence, as well as “direct” and indirect evidence. Specifically, AI-enabled visual neuroprosthetics—modern neuroimplants that combine artificial intelligence to stimulate the visual cortex and produce “artificial vision” for visually impaired individuals—can make a witness’s experience algorithmically constituted rather than merely a recording of the environment. Drawing on Andy Clark and David Chalmers’ extended mind theory and a dynamical-systems criterion of ongoing, bidirectional coupling, we argue that when perceptual content results from a continuous, tightly coupled human-device interaction that functionally replaces a sense, the outcome is the person’s own perception. Based on this, when a human-algorithm unit whose perception relevant to the trial is materially shaped by AI—an “AIWitness”—courts should regard the witness’s testimony as eyewitness evidence, rather than a separate machine output. The law should not dismiss extended cognitive systems merely because part of cognition occurs outside the skull. Grounded in principles of equality, participation, and fair trial values, this normative account upholds the status of disabled citizens as witnesses and not merely data sources.

AI-enabled neurotechnologies; eyewitness testimony; evidential law; artificial intelligence; technologically-mediated perception; intracortical visual neuroprostheses; extended mind

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn Reddit

Reddit Bluesky

Bluesky